Deontological

& Kantian Ethics

This strain of

moral reflection that argues that moral treatment is appropriate to

humans because of their rationality has a long history. Its most popular

recent incarnation is associated with the moral thinking of the

philosopher Immanuel Kant. His view is of a type called

“deontological” because it aims to show how there can be moral

requirements that do not depend on whether the actions required produce

good consequences.

Kant took it

be our special competence as rational beings to formulate general or

universal laws, which is what gave us moral knowledge. For any act that

we might contemplate doing, we can always ask whether we would be

willing to endorse a universal law that permitted or required that type

of action. Interestingly, such questioning is strikingly like applying

the Golden Rule to a prospective action. If I contemplate cheating my

neighbor, Kant would have me ask myself whether I would be willing to

live in a world in which people were all permitted to cheat one

another--which, of course, would mean that I too would be subject to

permissible cheating. With perhaps an excess of optimism, Kant concluded

that, not only would no one want to live in such a world, no one could

honestly will to live in one. If then, I proceed to cheat my neighbor, I

live out a kind of contradiction: I perform an action that I would not

allow generally, an action that I cannot endorse as a general rule.

Thus, I know at least in my heart of hearts that I am making a special

exception for myself that I would not grant others, and that I cannot

really justify for myself.

|

|

Note that Kant

is not saying that I shouldn’t cheat my neighbor because doing

so might lead to my getting cheated myself. Kant is proposing a

test that one performs wholly in one’s mind. I ask myself if I

could will my intended action as a universal law. If I cannot,

then that action is wrong even if I was perfectly sure that I could do

it and suffer no bad consequences at all.

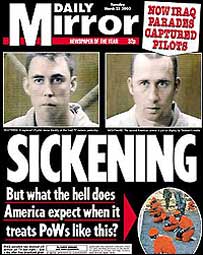

Image at left from BBC,

When are pictures of POWs propaganda? (discussing status of

detainees in camp X Ray compared to the American reaction to POWs

captured in Iraq being photographed) More info below

|

Kant thought

that this competence of ours was more than merely a means to figure out

what is moral. Since he took it to derive from our reason alone

and not from our desires, he thought it represented our unique freedom

from natural forces. Human beings could guide their actions, could

decide which of their desires to act on, by reference to a standard

found in their reason and not thus itself the product of desire. Thus,

in our reason, Kant found freedom, freedom from the forces of nature,

freedom from the pushes and pulls of desires and aversions. Thus

his moral theory exalts human beings’ free rational wills, and teaches

us to treat all free rational beings as “ends-in-themselves,” that

is, as beings that cannot rightly be subjected to forces that their own

reason does not endorse. This in turn adds a new dimension to the

test described above. When I ask of a prospective action, would I

willing to live subject to a universal law permitting or requiring such

things, I am asking do I truly believe that all rational beings could

freely endorse the action I have in mind.

When I

contemplate cheating my neighbor, what I must ask is, “Could my action

be freely and rationally endorsed by my neighbor?” It is obvious

that it could not, since the very possibility of cheating my neighbor

requires bypassing her rational judgment about what I am doing. I

must depend on her ignorance of what I am doing in order to succeed in

cheating her. Likewise, robbing my neighbor requires bypassing or

overriding her freedom. I can only rob her by acting against her

will--if it were her will that I end up with the thing I rob, then she

would give it to me and it would not be robbery. Consequently,

morality of this Kantian variety is sometimes identified with respect,

respect for the freedom and rationality of one’s fellows. Evil

actions are actions with bypass or override or ignore the freedom and

rationality of others, and thus are disrespectful of those others’

most distinctive capacities. And such a moral view is

deontological in that it arrives at its judgments without considering

all the consequences of the acts under consideration. So, even if

cheating or robbing my neighbor might in some way help my nation or even

all of humanity, such acts are forbidden because they fail to respect my

neighbor.

In sum, for

Kant and those inspired by him, true morality is a matter of treating

human beings in ways that are appropriate to their nature of free and

rational beings. And this means in ways that treat them as

free and rational, in ways that they can freely and rationally accept.

When people complain, for example, of being treated like objects or like

tools, they are essentially saying that they have been treated in ways

that fail to respect their freedom and rationality. They have been

manipulated or pushed around, rather than appealed to for free and

rational acceptance. Since freedom and rationality are taken to be

the marks of personhood, a Kantian-type morality is sometimes

called a morality of respect for persons.

Contrary to

consequentialism, this kind of moral approach clearly rules out using

people as means to the happiness of others. For this reason, many of

those who have felt that utilitarianism is not a strong enough defender

of individual human rights, have turned to Kantian or Kantian-inspired

moral views. Nonetheless, though there is undoubtedly something

about Kantian-style morality that resonates with many people’s strong

feelings about the treatment proper to human beings, this kind of

approach has its problems as well. Unlike utilitarianism with its

emphasis on happiness or the satisfaction of desires, Kantian moral

theory doesn’t provide an easily-grasped notion of the good. The

idea that certain treatment is appropriate to free rational beings is a

more abstract kind of good than pleasure or satisfaction, nor is it easy

to prove that it is more important to respect human beings than to bring

about their happiness. And many philosophers have doubted whether

we really have a capacity to make rational evaluations independent of

our desires.

|

Ethics Updates: Kant and

Deontology: includes Powerpoint presentation and

Real Media resources in addition to a variety of reading about Kant and

Deontological Systems.

Notes

on Deontology is a helpful introduction; it discusses the history of deontology,

and the methods of applying the philosophy

to decisions, particularly the universalizability of moral principles.

The

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy has an entry on Duties

and Deontological Ethics.

| It is often mistakenly

said of Kant, that the full content of morality could be derived

from our pure reason without reference to the facts of the world.

Far from it. Reason supplies a test of morality, but it is our

desires that supply the subjects of the test. My reason cannot

itself tell me not to cheat my neighbor. Rather, observing in myself

the desire to cheat him, I can apply reason to this desire and ask

if I would be willing to live in a world where everyone was

permitted to act on such desires. It is the test that is universal

and derived from reason, but the test must be applied to the

observed facts of human life. |

Another helpful

site discusses the meaning of deontology and compares it to other theories such as

consequentialism.

There's an additional discussion

about the role of consequences of actions in the area of deontological

ethics and a brief essay outlining the deontological

objections to consequentialism.

|